An American Soldier’s Journey Home

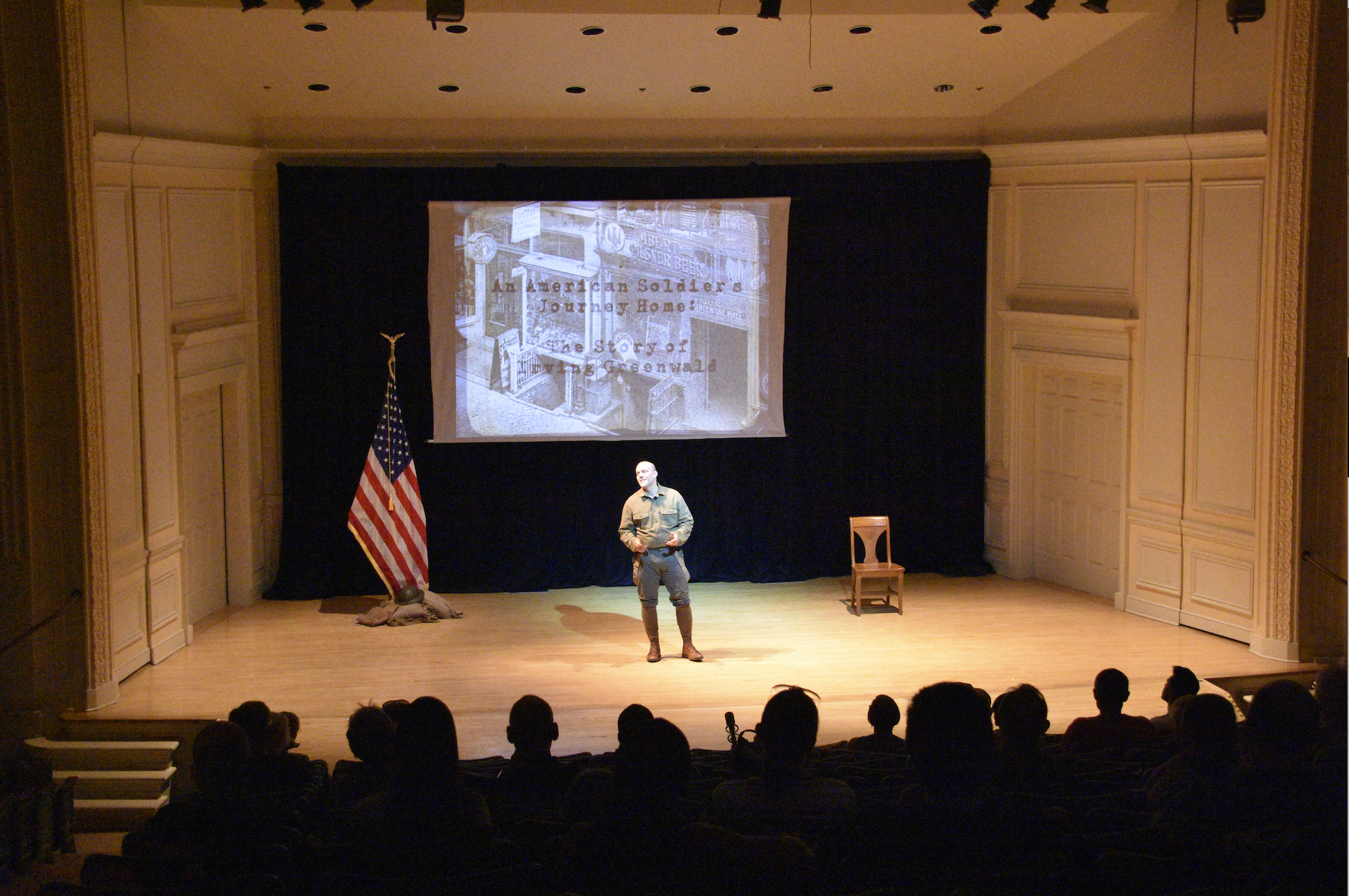

I was commissioned by the Library of Congress’ Veteran History Project to adapt Irving Greenwald's diary into a play. Greenwald, a soldier from World War I, was part of the Lost Battalion. The Project was to commemorate the end of the First World War and the signing of the Armistice in 1918. I performed the play at the Library of Congress twice, on Veterans Day and Memorial Day 2018.

“I stand with bated breath waiting for the explosion of the shell. I imagine the toll of injury and death it takes. The cost of it. The futility of it. The war will never be won on the field of battle. Why not end it all and spare men and women.”

- Irving Greenwald

Audience reactions after my performance at the Library of Congress on Veteran Day

Audience reactions after my performance at the Library of Congress on Memorial Day

“Taurel vividly conveyed the intensity and terror of trench warfare, the jubilation of the troops following the Armistice, and Greenwald’s love for his family, particularly his wife, Leah. Taurel’s performance was a moving demonstration of what can happen when families choose to give materials to VHP.”

- Megan Harris, Veteran History Project, The Library of Congress

The man who inspired the show

Irving Greenwald

-

He was a Hungarian Jew, who grew up on the upper east side of New York. Drafting into the United States Army in December of 1917. He fought in the Argonne Forest and was in E Compnay of the 308, part of the 77th Division. Famously knows as the Lost Battalion. The bloodiest, and most costly engagement in the First World War for our Doughboys.

Cut from their regiment for six days, and surrounded by Germans, and enduring intense fighting bombing in the Argonne Forest of France. Roughly 197 were killed in action and approximately 150 missing or taken prisoner before the 194 remaining men were rescued. Food was scarce and water was available only by crawling, under fire, to a nearby stream. Ammunition ran low and they were even bombarded by shells from their own artillery. In an infamous incident on 4th of October, inaccurate coordinates were delivered by one of the pigeons and the unit was subjected to friendly fire. The unit was saved by another pigeon, Cher Ami, delivering the following message,

“WE ARE ALONG THE ROAD PARALLEL 276.4, OUR ARTILLERY IS DROPPING A BARRAGE DIRECTLY ON US. FOR HEAVENS SAKE STOP IT!”

See his official documents at the Veteran History Project’s Website.

-

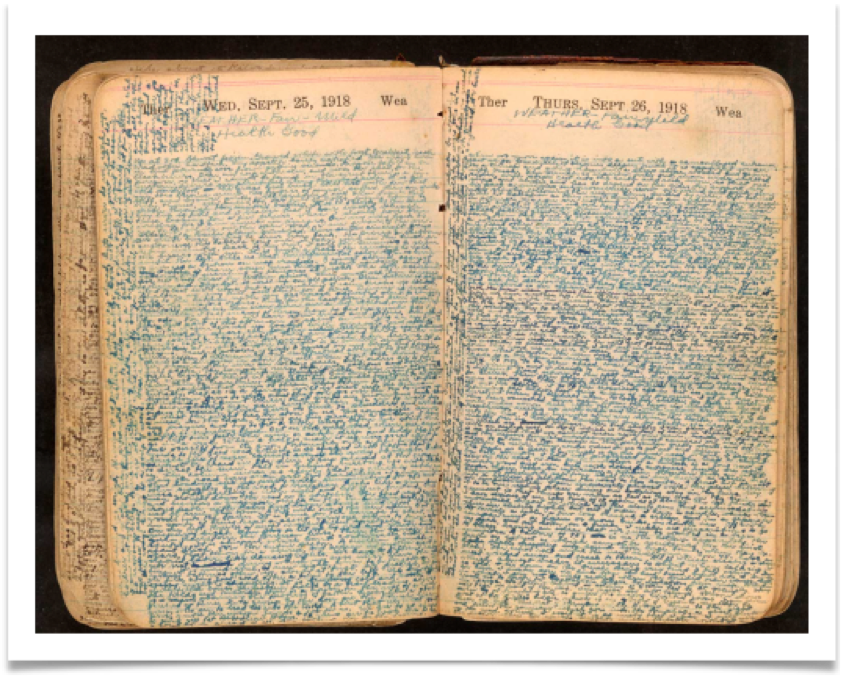

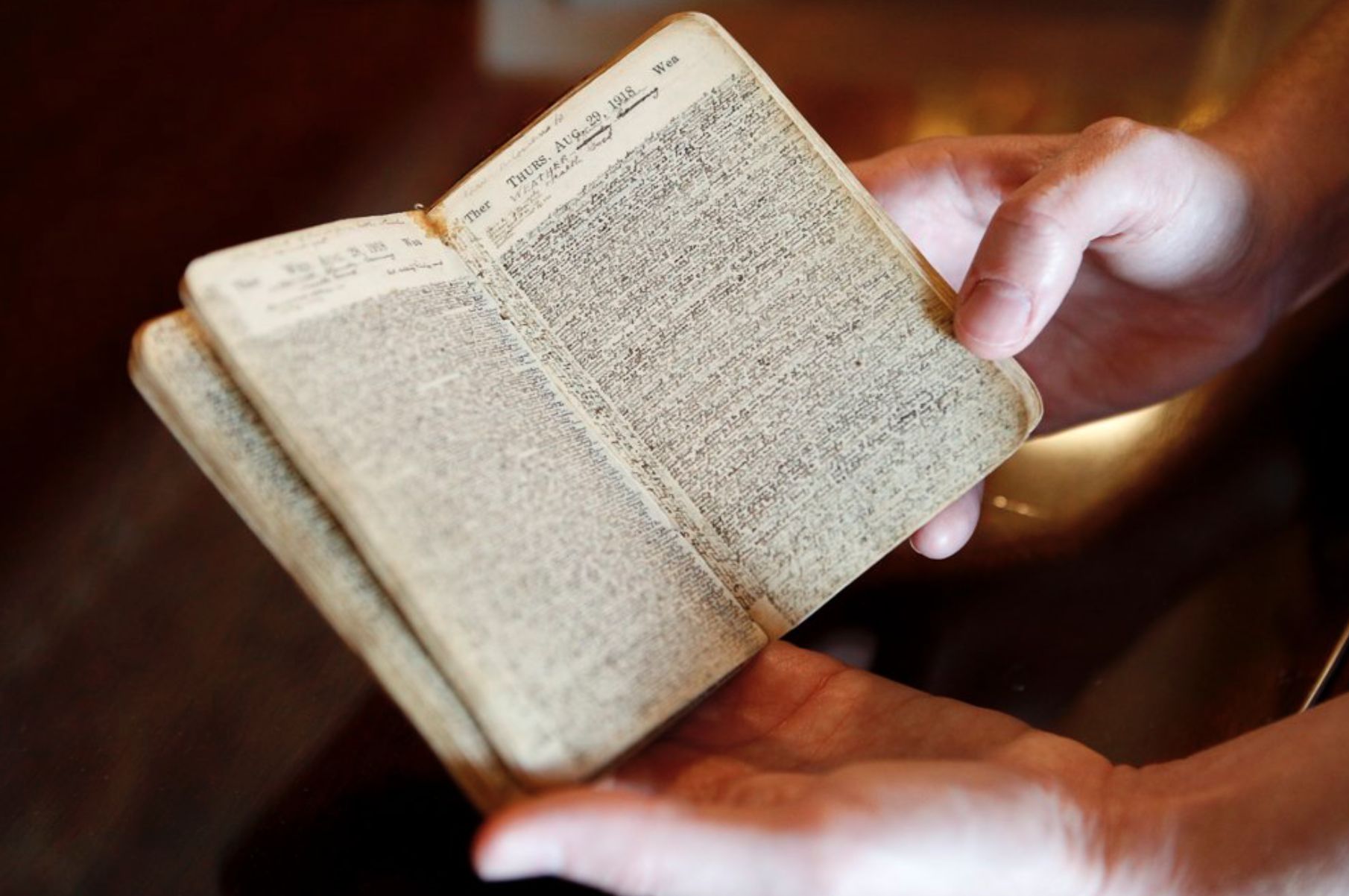

Greenwald, who served with the 308th Infantry Regiment during World War I, kept a detailed diary that is the centerpiece of the collection at the Library of Congress and of the play. The content of the diary is breathtaking. Greenwald wrote his entries in the tiniest of handwriting, eloquently relating his experiences in training, in combat, and in the hospital after he was wounded in October 1918. The diary was transcribed by his daughter and sister in the late 1930’s.

How I created the play

The play is 85% of the diary of Private Irving Greenwald exact words, I took 465 days of his diary entries and condense them into a moving and thought provoking 60 minute play.

-

Reading a soldier’s diary requires a tremendous amount of patience. For the soldiers of the First World War, the actual fighting took up a minimal amount of their time. In reality, the life of a soldier in war is filled with a tremendous amount of minutia. Reading a soldier’s diary requires time to digest all of that soldier’s life while in service, from his day-to-day life in training, through what it means to endure life in the trenches and to muster heroic courage in combat.

For the Library of Congress’s commemoration of the centennial of the First World War, I was invited to write a new play based on the life of Irving Greenwald, a soldier from WWI. Greenwald was part of the Lost Battalion, and the Library’s Veterans History Project preserves his diary. I will perform a one-man play on Veteran’s Day.

Irving Greenwald left 465 days of his diary entries, and I set out in May to read all of them, to read ten days’ worth of his diary entries each day. I aimed to complete the entire diary in a little over a month. Some days I read more, and some days I read less.

Luckily, since Greenwald’s diary had been digitized, the process was simple—much easier than my last project, The American Soldier. That play is based on letters written by veterans from the American Revolution all the way through current day Afghanistan, taking eight years to research and write. I researched individual letters, mostly at the New York Public Library, and photocopied passages from those letters I found especially compelling. I sorted them into folders of letters about the Vietnam War, WWII, the Iraq War, the Revolutionary War, etc. I typed them up by hand—tedious and time-consuming—before finally fleshing them out into monologues that I could work on as an actor.

But because Greenwald’s diary was digitized, I could turn the whole thing into a PDF, upload it to my Kindle. I could then highlight passages I found compelling and pull out only what struck me into one document, and that would become the foundation of the play, An American Soldier’s Journey Home. To find the best parts of the diary, I had to read it—every single page of it.

Greenwald, fortunately, was a very eloquent writer, so there was plenty to pull from, even in moments that weren’t thrilling. I sorted the passages under basic headings like Camp, Food, Funny, Death, Trench, and more. I used a color-coding system: red meant this was important, and green was a cue to stop and re-read the material.

-

By early summer, I had the diary sorted into five basic sections: his camp life, being shipped off to France, arriving in Europe, his trench life, and his time in the hospital after being wounded. It took another month to tease out all the best passages of a particular topic. The play could not be longer than 45 to 55 minutes, so my challenge was to trim down the word count to trim down the run time. I knew that my last play The American Soldier was only 7,500 words, and it ran 57 minutes. I had only about two more months to finish my play and was at nearly 30,000 words—more than 20,000 words too many. The hardest thing to do in writing, especially when it is poetic and eloquent writing that you have fallen in love with, is deleting. I stayed up late many nights reading and re-reading, trying to get a feel for how I wanted to tell Greenwald’s story. By August, I had the draft down to 17,000 words. I kept repeating to myself, Get to the point, Douglas, get to the point!

I took about a week off to digest the material, and then I began editing again. By the end of August, I had the draft down to 15,000 words. From there, I moved passages around and added just a bit of connective tissue to help Irving’s writing take the shape of a fluid monologue. It was time to read it out loud, which is a critical step for getting a sense of whether a play is working. So I started reading this early draft out loud to my wife and a few others, and something still felt off.

It is a frightening feeling as a writer when you feel stuck and can’t move the story forward. I have lived through this feeling before, so I know it doesn’t last forever, but when you are in it, it feels as if you will never see the light at the end of the tunnel. I tried listening to music, something I lean on for inspiration. I looked at images of World War I—the people, the places. And at the beginning of September, an epiphany arrived: I knew how to tell my story. As if the writing gods said, OK, Douglas, you have suffered enough, and you may now move forward. Within one day, I was down to 5,800 words.

With this draft and being a month out from the show, I felt good about taking the play into my memory, crafting my character so that I could share the story of Irving Greenwald’s life in service just in time for November 11th, 2017.

-

Red meant the material was important, and Green meant to me to stop and re-read the material.

VETERENS DAY

Veterans Day is honored on November 11th because it marks the end of the Great War.

On November 11th, Veterans Day 2018 will mark 100 years when the last shot was fired on November 11th, 1918 at the 11th hour. My home town of Hoboken, New Jersey was the port that nearly all the soldiers would pass through both on their way to fight, and home from, the Great War. “The war to end all wars”, as it was coined when WWI started in 1914. Approximately two million American servicemen passed through Hoboken between the spring of 1917 and the fall of 1918 when the United States entered the war. “Heaven, Hell or Hoboken” became the national rallying cry for all the boys that they be home by Christmas of 1917. However, the war actually did not end until November 11th of 1918.

I took these images to help remember the spirit of the boys is still with us, and I believe still roaming the cobblestone streets of Hoboken. The photos were shot in some of the oldest parts of Hoboken that existed back in 1918. They were taken at the train station, the ferry terminal and in the alleys to help us imagine how it must have looked, and how it felt a hundred years ago as hese brave boys were getting ready to ship off, some to never come back home. My hope is that these photos help us all imagine the courage it must have taken these brave young men to leave home and fight in the First World War.

"A wonderful play and tribute to those who fought and served in World War One."

- Jari Villanueva, The Doughboy Foundation

World War I Living History Weekend At The National World War I Memorial In

Washington, DC

The Doghboy Foundation 2024

In 2024 I had the honor to perform my solo show, “An American Soldier Journey Home,” to help honor the amazing bronze sculpture “A Soldiers Journey” by Sabin Howard. A monument for “We the People” that honors those who fought in World War I. As Mr. Howard says it best, “it is a monument that honors and celebrates humanity.”